Confirmation bias: why we see what we want to see from tarot cards to neuroscience

Tahmid ChoudhuryHow often have you looked at your horoscope only to nod in agreement when it says you’re spontaneous, kind and highly intuitive? 😊 Or maybe a friend pulled out a deck of tarot cards and predicted that you’d buy a house soon; a few months later, after poring through real‑estate listings and sending countless enquiries, you find yourself moving into a new place and thinking “wow, the cards were right!”. 🔮 These moments are fun and charming, but they reveal something fundamental about how human brains work: confirmation bias. We are natural pattern‑seekers who tend to notice information that confirms our existing beliefs and ignore information that contradicts them. In this post we’ll explore confirmation bias from playful examples like tarot readings and sausage‑dog sightings to the deeper neuroscience behind the phenomenon, weaving in related biases such as the Barnum effect, the Baader–Meinhof frequency illusion and the self‑fulfilling prophecy.

What is confirmation bias? 🤔

Confirmation bias is our brain’s tendency to favour information that supports what we already think and to downplay or ignore information that challenges our beliefs. Psychologist Raymond Nickerson characterised it as the “tendency to seek or interpret evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs, expectations or a hypothesis in hand”[1]. Instead of acting like impartial jurors weighing all the evidence, we build a case for our preferred conclusion and unconsciously select which facts to admit[2]. Confirmation bias isn’t limited to politics or social media; it influences everyday decisions, from the food we think is healthy to the friends we choose and the hobbies we enjoy.

Before diving into neuroscience, let’s warm up with some light‑hearted examples. We’ll revisit horoscopes, tarot cards and star signs, then move on to the Barnum effect, Baader–Meinhof phenomenon and self‑fulfilling prophecies.

Horoscopes, star signs and the Barnum effect ✨

Most of us have flipped through a magazine or browsed an astrology app out of curiosity. The descriptions often feel uncannily accurate: “You have a need for people to like and admire you, yet you tend to be critical of yourself.” The trick isn’t supernatural foresight; it’s the Barnum effect. Named after showman P. T. Barnum, this effect describes how people interpret vague, general statements as uniquely tailored to them. Psychologists have noted that horoscopes use intentionally ambiguous statements that contain something for everyone[3]. Because we want to believe the reading applies to us, we ignore the parts that don’t fit and latch onto the ones that do. The same is true for tarot cards: vague phrases like “a journey is coming” or “you will face a challenge” are broad enough that we can connect them to almost anything in our lives. Research warns that when people make decisions based on such vague statements they risk misinterpreting coincidences as destiny[4].

Seeing sausage dogs everywhere: the Baader–Meinhof frequency illusion 🐶

Have you ever learned a new word and then suddenly heard it everywhere? Or maybe you saw a sausage dog on your way to work and then noticed dachshunds on every street. This is the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon, also called the frequency illusion. After we encounter something new, our brains selectively pay attention to it and we feel like it has become common. In the context of COVID‑19 research, clinicians experienced this effect when they read a claim that patients had “preserved lung compliance” and then began seeing such cases everywhere[5]. The article explaining this phenomenon notes that once clinicians were prompted to notice the category, their brains filtered observations to fit it[6]. The frequency illusion thus reinforces confirmation bias: we see more evidence for our belief because we notice it more often.

In everyday life, if someone mentions that sausage dogs bring good luck, you might start spotting these long‑bodied canines at parks, on social media and even on socks in clothing shops. The dogs were always there; your brain just hadn’t considered them meaningful until you started looking. Similarly, if a tarot card reader says you’ll buy a house, you’re more likely to browse property listings, ask friends for tips and attend open houses, making a purchase more likely. When the event occurs, you attribute it to the prediction instead of recognising the active role your expectations played.

Labels and self‑fulfilling prophecies: why we should be careful with words 🏷️

Confirmation bias isn’t confined to mystical readings; it plays out in classrooms and homes every day. When adults label children as “clumsy,” “lazy” or “gifted,” they inadvertently shape the way those children see themselves. Social psychologists call this a self‑fulfilling prophecy. A literature review on teacher expectations describes a process: teachers form expectations about students, act on those expectations, and students react, changing their performance accordingly. Teachers with low expectations may provide less challenging work or less encouragement; students pick up on these cues and perform worse, confirming the original label. The cycle is especially damaging when expectations are based on biases about race, gender or socioeconomic status. High expectations, on the other hand, can protect students and foster resilience.

The same principle applies to the labels we give ourselves. If you’ve ever thought “I’m bad at math,” you’re likely to notice mistakes more than successes and avoid opportunities to improve. By contrast, adopting a growth mindset - viewing abilities as skills that can be developed through effort - encourages us to interpret setbacks as learning opportunities. Words carry weight; by choosing labels carefully and focusing on behaviors rather than fixed traits, we can prevent negative labels from turning into self‑fulfilling prophecies.

From intuitive dualism to teleological thinking: cognitive biases and religion 🙏

Many religious and spiritual beliefs can also be understood through the lens of cognitive biases. Philosopher‑theologian Mohammad Biabanaki argues that humans are naturally predisposed to intuitive dualism, the belief that mind and body are separate and that some part of us (a soul) survives after death. Because we have difficulty imagining the cessation of consciousness, we readily accept ideas of an afterlife and spirits. Biabanaki also notes a teleological bias, our inclination to see purpose and design in nature. Children often infer that natural features like mountains or forests exist “for something” (providing shelter or beauty), and they are inclined to see intentional design behind them. This predisposition toward seeing purposeful design makes us receptive to the idea of a creator or divine being.

Confirmation bias amplifies these tendencies. People who believe in a protective guardian angel may remember close calls as evidence of divine intervention while forgetting times when nothing unusual happened. Those who see meaning in coincidences - such as dreaming about a friend and then receiving a text message the next day - are tapping into the same cognitive machinery that underlies the Barnum effect and frequency illusion. When combined, these biases create powerful narratives about destiny and faith that feel personally validated.

The neuroscience of confirmation bias: reward, reinforcement learning and the brain 🧠

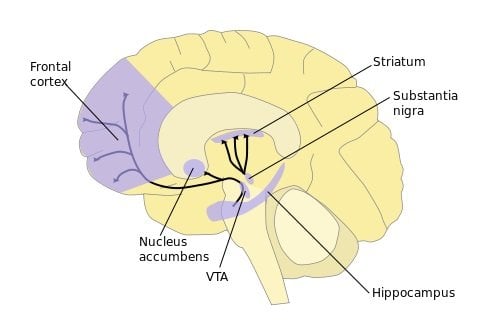

So far we’ve looked at everyday examples and psychological models. Now let’s peer inside the brain. Neuroscientists study confirmation bias through experiments and computational models. A 2024 paper by Bergerot and colleagues used reinforcement‑learning agents to show that a moderate level of confirmation bias - overweighting positive feedback relative to negative feedback - can actually enhance decision‑making in uncertain environments[7]. The researchers modelled the positivity bias, where people and animals learn more from positive feedback than from negative feedback. In the brain, this bias may be linked to dopaminergic signals in the striatum and prefrontal cortex that encode reward prediction errors. Overweighting positive outcomes can speed up learning when rewards are uncertain, but excessive bias leads to poor decisions[7]. This finding suggests that confirmation bias isn’t simply a flaw; it may be an adaptive mechanism tuned by evolution to help us learn from successes and ignore random noise.

Functional neuroimaging studies complement this view. When people evaluate information that confirms their beliefs, brain regions associated with reward and emotion, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum, show heightened activity. When faced with disconfirming evidence, areas linked to cognitive control and conflict monitoring, like the anterior cingulate cortex and lateral prefrontal cortex, become more active. This neural tug‑of‑war reflects the cost of adjusting our beliefs: accepting new information requires effortful control, whereas sticking with familiar ideas is rewarding and energy‑efficient. Over time, our neural circuits strengthen the pathways that align with our expectations, making confirmation bias self‑reinforcing.

Confirmation bias in the digital age 📱

Confirmation bias isn’t limited to tarot tables or classrooms; it also shapes our digital lives. Social media algorithms are designed to maximise engagement by showing us content that resonates with our interests. By curating our feeds based on what we’ve liked before, these platforms create echo chambers where our existing views are constantly reinforced, and dissenting opinions are filtered out. This can lead to polarisation and misinformation. When combined with the frequency illusion, we might believe that a fringe conspiracy theory is widespread simply because our feed shows multiple posts about it in a short time.

Search engines also reflect our biases. If you’re convinced that a particular health supplement works, you might type queries that confirm your belief (“benefits of supplement X”) and click on articles that support it. Search algorithms learn from your click history and will serve up more of the same, strengthening your conviction. Recognising these feedback loops is the first step to breaking free from them. Deliberately seeking out diverse sources, engaging with contrary viewpoints and using fact‑checking tools can help mitigate digital confirmation bias.

How to manage confirmation bias 💡

Confirmation bias is a universal human tendency; we can’t simply turn it off. But we can cultivate habits that make us less susceptible:

1. Practice critical thinking and scepticism. Before accepting information that feels right, ask yourself what evidence supports it and whether alternative explanations exist. Are you giving more weight to confirming evidence than to disconfirming evidence?

2. Seek out disconfirming information. Try to read articles from diverse perspectives, especially on controversial topics. In science, the principle of falsifiability encourages us to test hypotheses that could prove us wrong. As Nickerson noted, confirmation bias arises when we gather evidence to build a case rather than evaluate it impartially[2].

3. Adopt a growth mindset. When you catch yourself labelling yourself or others (“I’m clumsy”), reframe it to focus on behaviour (“I dropped my coffee this morning”). This reduces the risk of creating self‑fulfilling prophecies.

4. Be mindful of emotions. Strong emotions can heighten confirmation bias. When reading news or discussing sensitive topics, pause to notice how you feel and whether those feelings are driving your interpretation of information.

5. Use structured decision‑making tools. Checklists, pros–cons lists and evidence matrices help you systematically evaluate options rather than relying on gut feelings. In professional settings, practices like blinded peer review reduce the impact of bias.

By adopting these strategies, we respect our brain’s shortcuts while also cultivating humility and openness.

Conclusion: embracing curiosity and scientific thinking

Confirmation bias is both a playful and profound aspect of human cognition. It explains why we’re delighted when a star‑sign description “fits” us and why we keep seeing sausage dogs after someone points them out. It also sheds light on deeper issues, from educational inequities to how we interpret religious experiences. Neuroscience reveals that confirmation bias arises from the same reward circuits that help us learn; moderate bias can even be adaptive[7]. But when left unchecked, it can lead us to ignore critical evidence, reinforce stereotypes and fuel misinformation. By recognising our biases, seeking diverse perspectives and embracing evidence‑based thinking, we can harness the brain’s pattern‑seeking power without being deceived by it.

Let this awareness be your new “tarot card” - instead of predicting the future, it empowers you to shape it with curiosity, empathy and informed decision‑making.

References

1. R. S. Nickerson, “Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises”, Review of General Psychology, 1998 - defines confirmation bias as the tendency to search for evidence that supports existing beliefs and notes that people often interpret evidence selectively[1][2].

2. T. H. Bergerot et al., “Moderate confirmation bias enhances decision‑making in groups of reinforcement‑learning agents”, 2024 - explains that a positivity bias (overweighting positive feedback) can enhance learning under uncertainty and links it to reinforcement learning[7].

3. TNTP Practitioner’s Literature Review on Teacher Expectations (2024) - describes how teachers’ expectations create self‑fulfilling prophecies: low expectations lead to lower performance, while high expectations protect students.

4. The Decision Lab, “Barnum effect” - notes that horoscopes and tarot readings use vague statements that people interpret as unique to them, illustrating the Barnum effect[3][4].

5. L. D. J. Bos et al., “The perils of premature phenotyping in COVID‑19: a call for caution”, European Respiratory Journal (2020) - describes the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon (frequency illusion), where clinicians began seeing certain cases everywhere after being told about them[6].

6. M. Biabanaki, “The cognitive biases of human mind in accepting and transmitting religious and theological beliefs”, 2020 - discusses intuitive dualism and teleological bias, showing that humans naturally believe minds and bodies are separate and attribute purpose to natural phenomena.